In a 2014 opinion piece published by the New York Times, David Brooks wrote that the greatest creative minds “think like artists but work like accountants.”[1] Industry, discipline, routine and order are often necessary foundations for giving creativity a place to flourish. As a graduate of the Hispanic Theological Initiative (HTI) who now works in the HTI office, I have witnessed HTI’s pedagogical creativity from a number of vantage points: pre-dissertation fellow, dissertation fellow, Early Career Orientation participant, associate editor for Perspectivas, Open Plaza contributor, and now Assistant Director for Programming. HTI has been a significant force in my formation as a scholar and as a person. In addition, my background as a former business owner and manager helped me see HTI’s organizational genius from a perspective that adds to my experience as an HTI scholar. The daily grind that supports and encourages the creativity that results in what I will call “En Conjunto formation” is a less visible but indispensable aspect of everything HTI is and does. This brief reflection, therefore, will consider aspects of HTI’s organizational culture and daily activities before moving to its pedagogical innovations. Although creative and industrial dispositions often feed each other in several contexts, it is often tempting to praise creativity as if it was a purely spontaneous, disembodied activity—without providing an account of the material labor that sustains it. To use David Brooks’ analogy, HTI’s pedagogical “artistry” is undergirded by disciplined “accountant” work.

A well-rounded view of HTI recognizes that, as a non-profit organization that continues to impact theological and religious education, HTI is at the tricky intersection of ministry and business. The day-to-day operations of the HTI office involves managing teams, guiding projects, fundraising, grant writing, balancing budgets, meeting with administrators, planning events, facilitating committee meetings, casting vision, strategizing future initiatives, executing current initiatives, developing programming, assessing and reassessing professional development courses, editing publications, updating websites, data analysis, garnering feedback for necessary adjustments of services, tracking documentation for fellowships and programs, and more. It also involves pastoring individuals, opening space for community, praying for those who are facing life struggles, finding ways to help constituents materially, celebrating every hire and promotion, rejoicing with marriages and births, crying with those suffering, checking in with people to see how they are doing, encouraging folks not to give up from writing their dissertations and/or going through with their tenure process. The lsit is long! To speak about HTI is to speak about both the more visible and less visible aspects of this organization that has helped transform the boarder landscape of theological and religious education for the last twenty-five years.

There is one fundamental aspect that runs through this multifaceted reality that HTI inhabits: a deep concern for reflecting the voices of HTI constituents. If you are not familiar with HTI, this may sound easier than it actually is. HTI is a multilingual, multiethnic, multifaith, multinational, multiracial, multidisciplinary, multigenerational, and ecumenical organization that includes a consortium of twenty-four PhD granting institutions positioned in different points of the ideological, theological, and political spectrum in the United States. This unusual difference was voiced by a number of leaders in theological and religious education as we interviewed them for our “HTI25: Many Voices, One Story” project, which consists of short videos that we promote through our social media outlets. For example, Bill Bellinger, chair of the Religion Department at Baylor University, summarized this general sentiment well during his interview. Reminiscing about a member council meeting, Bellinger shared: “I remember sitting, thinking: You know, it’s pretty remarkable the diversity of people that are in this room and are all committed to this common cause. And that gives me hope.”[2] The HTI consortium, which has successfully created a space in which difference can be sustained and celebrated around a common goal, is being recognized by leaders from different backgrounds as a model for the broader ecology of theological and religious education. A proper reflection of the newness or innovation that HTI brings must consider a basic disposition that helps sustain this reality: a constant concern for listening to the harmony coming out of the cacophony of voices of HTI constituents.

At its core, this constant effort to reflect the voice of the community, rather than of a small subset of individuals within a community, is the spirit of HTI’s En Conjunto way. In an extremely polarized world, it remains difficult to imagine spaces in which white evangelicals and womanist scholars join forces, queer theologians and conservative thinkers work together, and a space in which people from fifteen Christian denominations and three faith traditions—and no faith tradition—feel like they belong, because they do belong. HTI represents such space. This radical difference forces HTI to engage intentionally in constant reflection, assessment, and re-assessment of its programs and initiatives. That is partially because HTI does not attempt to format its scholars and constituents into a particular outcome. Mark Labberton, the current President of Fuller Seminary, commented in a recent interview that:

One of the things that I have been impressed by over the years (in) both the people that I know of at Fuller that have been directly affected by HTI but also on a broader national scale is that they (HTI) have not had a stereotyped kind of person that they are trying to work with. They are trying to find the right people that are ready for the kind of theological education and development that HTI is wanting to support, but they are not carbon copies of a ‘brand’ called HTI. They are supporting diverse students, who happen to be Latino/a(/x), and to me that is one of the great strengths and evidences of the thoughtfulness of what they are doing.[3]

Despite the implicit and explicit challenges posed by diversity language and contexts, HTI does not drive an intentional plan to express the difference of its constituents by the lowest common denominators. Rather, it celebrates differences and sees it as part of its identity—both in its comfortable and not-so-comfortable expressions. As such, the En Conjunto way brings, on one hand, a model for working with and from radical diversity, and it represents a constant challenge to continue to create community, on the other. As HTI grows, so does the need to listen to more voices. As more voices find a home in HTI, so HTI grows.

HTI’s constant effort to reflect the voices of its diverse community is not only a model of cooperation for a divided world, but it is also effective in terms of the value this effort brings to organizational culture and practice. Several works on the literature on leadership and business models argue that, in general, the success of organizations is strongly correlated to their ability to incorporate the voices of team members into its initiatives and projects. For example, in his book Superminds, MIT professor Thomas J. Malone demonstrates that teams are consistently smarter than individuals. James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of the Crowds argues along similar lines and, more recently, L. David Marquet’s Leadership is Language claims that the effectiveness with which “voice” is shared in a team largely accounts for a team’s success. Marquet even provides a formula for calculating the amount of “shared voice” in a team, which he calls “Team Language Coefficient.” To quote Jan Love, Dean of Candler School of Theology at Emory University, HTI is “a genius organizational effort that really paid off.”[4] The En Conjunto way is not only a model for nurturing and celebrating difference but also an organizational model that businesses try to implement in order to be more effective.

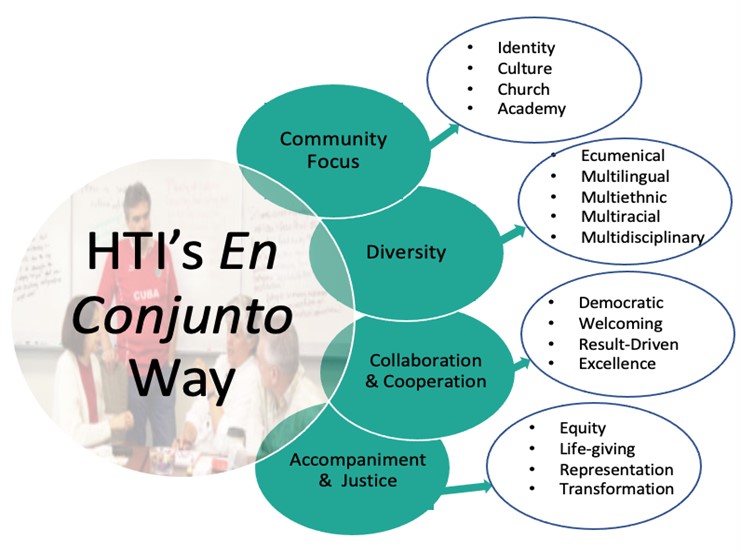

But of what does the En Conjunto way consist? Can we bottle it? Can it be made a product for the consumption of others—thus following the market’s temptation to package, buy, own, and sell? My sense is that HTI’s En Conjunto way can be described but not easily emulated partially because of the intangible elements of its community. En Conjunto springs not only from a planned organizational model, but also from social, cultural, and spiritual capital only available at the intersection of particular forms of difference. One way to describe En Conjunto is by categorizing key characteristics and subcategories (see chart below). These characteristics would be: 1-community focus: HTI is at the intersection of Latinx identities and cultures as well as of church and academy; 2-diversity: HTI is ecumenical, multilingual, multiethnic, multiracial, multigenerational, multidisciplinary, and multinational; 3-collaboration and cooperation: HTI draws a significant portion of its quality from its combination of result-driven excellence with its democratic and welcoming disposition; and 4-accompaniment & justice: HTI’s mission is rooted in Latinx struggles for transformative, life-giving equity and representation. When students and faculty connect to HTI, this En Conjunto ethos and spirit inhabits aspects of their work and study. That means that HTI’s En Conjunto way socializes constituents into a way of being. In their connection with HTI, constituents internalize not what to teach but a way of teaching; not what to say to peers, but a way to build community; and so on.

That is partially what Serene Jones, president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City, meant when she said in her HTI25 interview that:

The scholars that come out of HTI and go on to do the work of scholarship, teaching, formation, and ministry in all variety of contexts, because of how they’ve been formed, not only reach out and create the possibility for students to be similarly formed, (but) they create spaces where that formation is not considered unusual, but it is considered par for the course. And that space is a space in which multiple Latinx voices are heard, valued, and affirmed. And that is absolutely critical for the intellectual life of theological education in the United States. It raises the level of excellence for everyone when voices are strengthened in that space and encouraged.[5]

Jones elaborated on how HTI’s way of forming fosters innovative thinking. She said:

I would say that the most important space that (HTI) creates is a space within the imagination of the community; where new things can be imagined, new theological concepts come forth, new notions of community are generated, new possibilities for what it means to be church are born and tested. And that space of imagination you could never take for granted; it has to be cultivated, it has to be protected, and it has to be constantly reinvigorated. And so that space of imagination is absolutely crucial.[6]

Such space is also one where grounding in communal questions reveals ways in which scholarship must be challenged to be relevant to current contexts. Womanist theologian and dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School, Emilie Townes, said in the HTI25 interview that:

What I hear all the time is “oh, higher education is not relevant. It doesn’t speak to the needs of the people.” Well, that’s true if you’re not asking questions that relate to the society you live in. But look what happens when you work engaged with folks that are deeply connected to the worlds in which they live. And that’s where HTI comes in, helping us understand that the world is so much bigger than what we can imagine, and the questions we ask are necessary to make our society better.[7]

As we can see, the En Conjunto model has been recognized by leaders in the academy, as well as leaders in theological and religious education as a way of forming scholars that make a positive impact in classrooms, guilds, faculties, churches, and broader society.

Readers familiar with the work of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire may have noticed overlaps between HTI’s En Conjunto model and Freire’s critical pedagogy—especially in regard to Freire’s criticism to what he called the “banking model of education.” As Freire contended the banking model was characterized by a strongly hierarchical framework in which “specialists” must “deposit” knowledge into the students—who are seen as mostly passive recipients of the specialists’ agency. Seen from the prism of minoritized bodies in the US academy, this dynamic often means a white, Anglo-American man playing the role of specialist and thus trying to “deposit” white knowledge into the student. Recently, during HTI’s 2020 Book Prize Lecture, Luis Rivera-Pagán provided a brief illustration of the pedagogical model that has been predominant in the US academy. Reflecting on Peter Mena’s work, Rivera-Pagán, now Henry Winters Luce Professor in Ecumenics Emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary, reminisced about his own journey as a Ph.D. student:

The originality of Peter Mena’s book is to masterfully link the desert of the Bible and of the early Christianity monks with the desert and the diverse Borderlands of Gloria Anzaldúa. Again, this is something that the director of my doctoral dissertation at Yale, the magnificent historian of Christian theology, Jaroslav Pelikan, would never conceive and even less approve.[8]

When the predominant pedagogical model in the US academy remains unchallenged, forming scholars means forming them into a particular mode of Anglicized whiteness. HTI, however, represents a space in which a loving and productive resistance of colonial dispositions engrained in our educational systems is sustained. To use the words of Willie Jennings’ hope for the future of Western education, HTI is already “a gathering that recalibrates journeys and turns us away from the limited colonial options for knowing and living with each other.”[9] HTI overlaps with Freire’s critical pedagogy most strongly by moving away from a “banking model” and colonial pedagogical dispositions and by helping form scholars into a pedagogical community that exercises mutually transformative relationships within academic settings. In this sense, HTI’s En Conjunto formation does not name a rigid formula of forming people into a particular outcome, but an intentional openness to enter into a journey of mutual formation, with all its accompanying risks and hopes.

HTI’s En Conjunto formation points to hope. The hope of being able to work together, to learn from each other, to face the discomforts of being transformed by community, to re-think pre-conceived notions about companions in the journey. Arthur Holder, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs at the Graduate Theological Union, expressed the hope of HTI’s En Conjunto model when he noted that:

For me, the fundamental question is “what kind of world we want to have in the future? And how can higher education contribute to making that dream of a world that we want to have happen come to pass?” And for me HTI is the answer to that question not just for people in the Latinx community, but it’s the kind of higher education that I want to see to help prepare for the world that I want my children and grandchildren to live in. A higher education that is close to the needs of the community; the many communities that it serves; that has an integration of not just theory and practice, but different kinds of theories and different kinds of practices woven together into that kind of tapestry that reflects the many different threads, strands of the communities that are already here and that are coming to be. So it is not, for me, a matter of choosing how are we going to do a good job of supporting Latinx scholars or how are we going to do a good job of supporting other scholars from other groups. It’s like: HTI has provided the advanced outpost on the frontier that will help everyone. If we can develop, as a community of scholars, to be more like what HTI is, that is going to help everybody because that what you want is for people—wherever they are coming from, whatever their background is—to be able to stay rooted in that and then to reach out and make connections with all kinds of other people and put their creativity to work for everybody’s benefit. And seeing that happen in one community then sparks the possibility for that to happen in other communities as well.[10]

The hope of the loving and productive resistance of HTI’s pedagogical model resonates with the voices that are concerned with justice around the world—especially those who are convinced, as many of us are, that the construction of a new world must pass through educational formation. As a mutually-transformative pedagogic community, HTI provides a corrective to particular colonial anxieties insistently present in Western educational systems. HTI’s En Conjunto formation is a pedagogical model that has not only worked for the past 25 years but one that also challenges broadly-conceived educational systems to shake their colonial underpinnings.