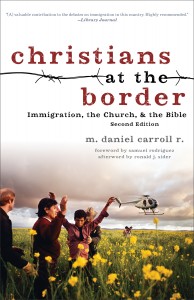

1st edition: M. Daniel Carroll R., Christians at the Border: Immigration, the Church, and the Bible, Baker Academic, 2008. 176 pages. $16.99.

Immigration, both legally sanctioned and undocumented, continues to be a divisive issue that affects not only political parties but also church communities. Aware that there is a chasm between Christians who favor more immigrant-friendly policies and Christians who advocate for stricter immigration laws, Daniel Carroll seeks to bridge this divide by providing a biblical foundation from which Christians across the political and ecclesial spectrum can dialogue explicitly as biblically informed Christians. By making the Bible a primary interlocutor for a discussion on immigration, Carroll wants to redefine the starting point of the debate. Thus, he invites Christians to begin not from ideological, racial, economic, or nationalistic perspectives, but from what could be called a “divine perspective” in light of scripture.

True to the author’s expertise in the Hebrew Scriptures, the book shines in its brief but engaging treatment of biblical passages that narrate both the experience of immigrants and the response to immigrants in the ancient scriptures. For example, Carroll details the story of the Moabite woman Ruth, who, after the death of her husband, an immigrant from Bethlehem, decides to return with her mother-in-law Naomi to Bethlehem where Ruth becomes a poor immigrant in a foreign land. Despite the fact that the law was not favorable to Moabites, Ruth encounters hospitality, remarries, and her ancestors become an essential element in the lineage of King David and eventually in the lineage of Jesus.

The stories of individual migrants (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Ruth) in the Hebrew Scriptures are complemented by a broader analysis of the experience of forced migration and exile that the Hebrew people endured in Egypt, Babylon, and Persia. As with contemporary wars and violence that continue to displace people around the world, the empires of Babylon and Persia displaced whole generations of Hebrew people who had to navigate and negotiate their presence and identity in a land that was not their own. Using particular examples from Ezra, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and other texts, Carroll nuances the varieties of approaches that were employed by Jews in order both to assimilate culturally as well as to ensure the preservation of their tradition(s).

Carroll’s more systematic analysis of key biblical concepts related to human displacement, whether chosen or forced, centers on the tradition of hospitality and the laws concerning sojourners. As one would expect from a biblical scholar, Carroll engages in a sustained interrogation of the law as understood in its own biblical context, and of the term “sojourner,” which in Hebrew can refer to any of four different terms that carry multiple connotations about who or what it means to be a foreigner. Special attention is given to the term gēr, the term most often translated as “alien,” “resident alien,” “stranger,” or “sojourner” (101, 1st ed.; 86, 2nd ed.).

The author’s focus on immigrants, foreigners, or refugees in the New Testament is much shorter, perhaps because these stories are more commonly known. For example, most people may be familiar with the reality that Jesus became a child refugee in Egypt because his life was under threat by the violence of Herod, or with the fact that Jesus pushed the acceptable boundaries of his tradition by engaging directly with both Gentiles and Samaritans who were considered outsiders. As with his treatment of the Hebrew Scriptures, the goal in highlighting narratives from the New Testament is not to find a one-to-one direct correlation between their experience and contemporary experience. Rather, the goal is to reflect critically in light of scripture on the implications that these holy books have for the attitude that Christians are called to embody, especially in regards to the so-called “strangers” in our midst.

Perhaps one of the unique but underdeveloped contributions of Carroll’s book, especially in the first edition, is his treatment of Romans 13. Placed at the end of the book and dealt with in only a few pages, it raises the question of Paul’s command to submit to the laws of the land, an injunction frequently used by Christians against undocumented migrants who enter the United States without following the proper legal channels. Although this biblical argument may be more pronounced within Evangelical Christian churches, it merits a more extensive analysis for it touches a critical nerve in the immigration debate—the relationship between law and justice.

In both editions of this book Carroll argues that Romans 13 must be contextualized within the broader biblical witness and attitude toward migrants. Thus, Romans 13 cannot be a starting point for discussion, but a piece of a much larger biblical tapestry. But whereas in the first edition Carroll addresses this contentious passage simply by trying to contextualize it within a broader framework, in the second edition he shifts the tone to provide a stronger argument and critique. For example, in the second edition Carroll clarifies that the Pauline text asks Christians to “be subject” or “submit” to the established authorities, but does not say to “obey.” Even though the differences in these terms appear insignificant, in a society where the phrase “obey the law” is used repeatedly against immigrants, such a small terminological clarification can shift the argument. Carroll strategically titles this new section in the second edition, “Discerning submission, not blind obedience” (125).

While most of the historical and biblical content remains the same in the second edition, Carroll does provide an updated political context in the first chapter and improves the appendix and endnotes. In fact, the appendix and endnotes themselves are a significant resource for further scholarly engagement with the topic of immigration and its relation to church life and theology.

Christians at the Border is an accessible book that purposely avoids statistics and technical jargon in order to focus on stories and concepts that have the possibility of helping Christians migrate and encounter each other at the borders that divide them. The book is a helpful biblical primer for Protestants and Catholics alike, and an explicit reminder that the divine view of immigration may in fact be quite different from our own.

University of Notre Dame