As an undergraduate student I participated in an honors program about “vocation” and “discernment.” This opportunity exposed me to literature that largely used Calvinist or Kuyperian approaches to frame personal vocation in relation to the job market. According to these texts, one’s vocation was defined by one’s employment (cf. Reyes, 4). Yet as a person of color raised in a poor, migrant home I knew employment was elusive and at times even exploitative for my community. So why would I frame vocation within this capitalist mode?

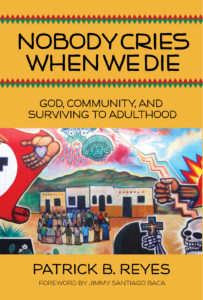

Nobody Cries When We Die: God, Community, and Surviving to Adulthood speaks directly to individuals with questions like mine. Using story as his primary analytic framework, practical theologian Patrick B. Reyes intervenes in vocational literature by asking what this notion means in a context where life—and, indeed, employment—are not guaranteed due to the colonial-historical realities people of color face. He posits that “Christian vocation is ‘God’s call to new life for all creation’…[so] living is our primary vocation” (Reyes, 13).

Reyes structurally advances this thesis by following the narrative of his life, emphasizing in it the theme of survival. It begins in his childhood and adolescence where he sustained physical abuse to protect his siblings while navigating gang-violence in his neighborhood—even witnessing the murder of a young girl right before his eyes. It moves to his time in higher education where he worked full time while studying within an academic system that did not believe in his scholarly ability or the intellectual contribution of his people. And it concludes with Reyes as an adult, wielding his Ph.D. to help marginalized students while colleagues question the legitimacy of his credentials precisely because he is Latinx.

In these stories community and land are facilitators of survival. Community is often epitomized in the text through Reyes’ grandmother, a woman who prayed for, cared for, and imparted wisdom on him. This woman “descended from holy people” and was one among many who God used to “call him to life” (Reyes, 65). Reyes conceives of this community through a theology of soil that stems from his time with Latinx field workers. In the fields one looks down at one’s footprints in the soil and sees the footprints of all those who work(ed) the land—that is, one sees one’s community. For Reyes, “these are the footprints through which God speaks to us” for in them lay the stories of our people, our struggles, who were birthed from this very ground (Reyes, 94). Though “ground” is shaped by history and power which dictate complicated conditions of work it is, for Reyes, the site of community which sustains the vocation of life.

Among its many contributions, the book powerfully demonstrates how story, land, and the realities of marginalized communities reconfigure our understanding of vocation. As a result, it challenges Eurocentric framings that center vocation around the job market. This makes Nobody Cries When We Die an invaluable resource for churches, community groups, and educational programs engaging questions of vocation . It offers stories that people, especially marginalized people, may resonate with and draw upon to build their own sense of vocation. Further, the book is a resource for undergraduate and graduate classrooms engaging practical, systematic, or liberation theology, and/or decolonial scholarship broadly. By foregrounding story, community, and the ways a historical-colonial matrix of power shapes physical land, the book challenges academic methodologies, providing an explicit example of theory/theology stemming from, and speaking to, quotidian communal experience. Aside from its provocative thesis, then, the book’s very presentation advances a claim on how academic work ought to be framed: as reflection on, and contribution to, life.

As a Latinx who resonates with much of this work, I believe Reyes overemphasizes “surviving” and “living” as the call of our communities. Vocation must also be about “thriving!” Yet, a call to “thrive” begets the question: What social conditions and structures need to change for our people to do more than merely survive? This is a live question. But Reyes’ methodology teaches that uncovering its answer requires embracing story, community, and land.

Union Theological Seminary