Sowing the Sacred is a sociohistorical and religious investigation “from below” that challenges dominant narratives of disempowered Mexican field workers in California. Centering the stories and testimonios of Apostólicos – a Oneness Pentecostal minority comprised of predominantly Mexican field workers, Lloyd Daniel Barba explores the myriad forms of religious expression, meaning-making practices, and theological imagination that defined this overlooked and often-vilified Pentecostal minority.

Barba’s writing style is engaging, clear, and unassuming. With the ease of an experienced story-teller, he takes the reader on a journey alongside the Apostólicos as he explores their patterns of labor and their unfolding story of migration and identity formation. Barba exquisitely captures the paradoxical relationship between the rise of anti-Mexican sentiments during the “immigration regime” (27), the utter marginalization of “Oneness” Pentecostals (3, 105), and the way in which Apostólicos resisted such oppositional forces by carving out spaces for themselves amidst inhospitable socio-political and physical landscapes.

The significance of Sowing the Sacred in the fields of history of religion and historiography at large, cannot be understated. Barba’s research approach and methodology effectively function as acts of resistance that defy traditional investigative methods that relegate minorities to invisible peripheries deemed undeserving of “proper” study or recognition. He specifically challenges Walter Goldschmidt’s model of “denominational stratification” (3) which demoted Mexican Pentecostal movements to the “lower level on the scale of formality” (1), and the national discourses from the 1930s that myopically centered the white-American migrant experience, i.e., the Dust Bowl/Okies migration (151), which attempted to erase the Mexican field-worker realities and the exploitative labor practices that became the backbone of California’s agricultural success.

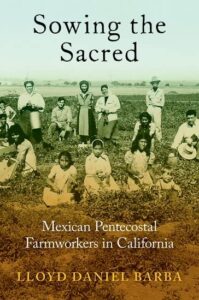

Barba’s historiography of resistance excavates the scorching fields and peripheries of California’s valleys to unearth the material records that, though absent from official archives, tell the story of an ostracized community who subversively transformed the profane into sacred sites of faith and belonging. With the extensive lack of Apostólico references in traditional archives, Barba turns to personal interviews, testimonios, hymnals, and other material artifacts such as photographs, church décor, and even obituaries—the entire book is peppered with these material artifacts—to unearth the cultural vibrancy and the creative genius that characterized the historically excluded Mexican Pentecostal field workers of California.

Barba doubles down on his centering efforts as he moves through the chapters. While chapters 1-3 center the transgressive and meaning-making practices that characterized the Apostólico movement at large, chapters 3 and 4 hone in on the foundational role that women played in a male-centered denomination that largely relegated them to the periphery. Against the backdrop of a machista ethno-religious culture, Barba masterfully re-inscribes into Apostólico history the undeniable influence of braceras; the women whose “labor of faith” (most significantly, their making and selling of tamales) funded their temples and sustained the upward mobility of men (149, 163). This skillful recalibration of Apostólica female agency makes Sowing the Sacred a significant resource for Gender and Chicana/o Studies, particularly his re-examination of gendered thresholds of space and power (154). No less important is his reconceptualization of seemingly exclusive dichotomies—sacred/profane, public/private, material/spiritual (74, 112, 154), and his collapsing of categories—mainly church-work-family (154-160), which women seamlessly traversed as they knit entire communities together.

Sowing the Sacred successfully places the sacred stories and laboring bodies of Apostólicos front and center, offering the reader not just a window into the past, but entirely new sets of lenses through which to examine, uncover, and admire the fruit of a completely different kind of “labor” that left a permanent mark on U.S. and Mexican history.

George Fox University